Harry Edwards: Framing a Century of Black Athlete Activism

April 3, 2017

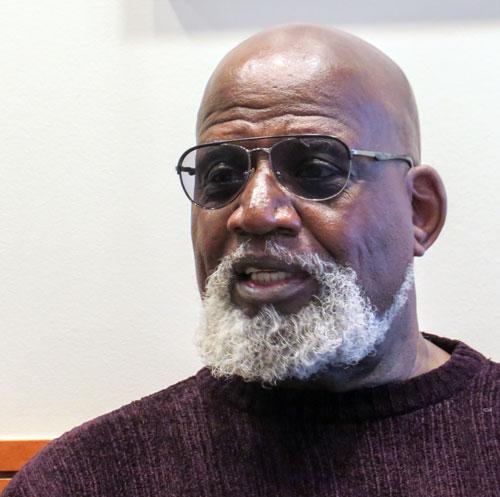

"There are no final victories; the struggle for legitimacy [by black and other nonwhite athletes] continues,” insisted sport sociologist Harry Edwards during his keynote talk as this spring’s Mark H. McCormack Executive in Residence. During his two-day visit to Isenberg on March 23rd and 24th, Dr. Edwards, an Emeritus Professor of Sociology at UCal Berkeley, spoke in Sport Management classes and met with McCormack program students and faculty. His hour-long keynote remarks, attended by several hundred members of the UMass Amherst community, explored over a century of activism by black athletes in America, including prospects for an era of likely confrontation triggered by a new Administration in Washington.

“We're on the cusp of a 5th wave of athlete activism, so don't be surprised when it washes over the shore," Edwards cautioned. If the new president implements the restrictive social services policies and police militarization promised in his campaign, “I absolutely guarantee you that athletes will be pressured to speak up. And what they will be pushing for will be beyond what we [have come to] recognize in terms of power.”

High-profile athletes, Edwards noted earlier in his talk, “have come to epitomize” societal beliefs, values, and sentiments. Sports, he underscored, “recapitulates” them. With their high-profile roles and “powerful personalities,” athletes become key influencers as spokespersons in society at large. That includes their evolving perspectives on long-enduring racism, which, Edwards added, has “metastasized into the problem of diversity [i.e., issues of discrimination and social justice accompanying its broader brush of ethnicity].” The final ingredient in this dynamic, he emphasized, is its articulation through traditional and social media.

Waves of Black Activism

Edwards’s remarks offered a history lesson that charted the course of black activism in American sports from the beginning of the twentieth century up to the present. He identified four separate waves of activism, anticipating a fifth on the horizon. Those waves, he noted, framed and were framed by their times.

First-wave pioneers like Jack Johnson, Jesse, Owens, and Joe Louis, he observed, pushed for recognition and legitimacy in a racist, apartheid society. They broke through to fame and recognition but ultimately paid unconscionable social, economic, and legal dues.

Following World War II, athletes like Jackie Robinson, Larry Dobby, Kenny Washington, and Chuck Cooper were catalysts for desegregation in American team sports. “[That] second wave went beyond legitimacy; it was about access,” remarked Edwards. “Jackie Robinson espoused nonviolence. He became black society’s Gandhi. He primed the pump for the Civil Rights movement.” Locker rooms gradually and painfully desegregated and America’s Negro leagues collapsed. At the same time, Negro colleges lost their mojo to recruit blue chip athletes.

A third wave with its Black Power movement sought social justice with attitude. Its premise: “Why should we play where we can’t work?” Iconic athletes like Jim Brown, Bill Russell, Muhammed Ali, and Curt Flood “actively challenged [the definition of] progress,” noted Edwards. Their public immersion in uncompromising activism drew social condemnation and criticism in the media.

Between the third and fourth waves, athletes like Michael Jordan and Charles Barkley dialed down activism, Edwards observed. “Republicans buy gym shoes too,” remarked Jordan. “I’m not a role model,” insisted Barkley.

Beginning around 2010, a fourth wave offered a very different narrative. Marshalling unprecedented independence and influence as mini-corporate entities and social media maestros, high-profile athletes espoused ideologies of Black Lives Matter and related causes. 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick took a knee during ritual performances of the National Anthem; University of Missouri football players got results via their protests against racism. But those and other athletes who went public, cautioned Edwards, continued to place themselves in risk’s way.

Activist, Mentor, Scholar

Dr. Edwards himself has exceled as a mentor and activist from the third wave on. A former scholar-athlete at San Jose State College, he orchestrated the Olympic Project for Human Rights, which encouraged African American athletes to protest the 1968 summer Olympics in Mexico City. The protest, which underscored persisting civil rights inequities in the United States, inspired Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ iconic black power salute during the medals ceremony. More recently, Edwards has lent inspiration and support to San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s protests. A long-time consultant to the team, Edwards has been an intellectual mentor to Kaepernick.

"Dr. Edwards is a true visionary.” Edwards earned his Ph.D. in sociology in 1972 from Cornell University, where he joined its faculty and wrote seminal works on the sociopolitical struggles of black athletes in America. “In our department, students are introduced to Dr. Edwards’ work in their very first year. . . He is a public intellectual in the tradition of W.E.B. Dubois,” remarked McCormack department chair Janet Fink in introducing the keynoter. “Over the past fifty years,” she added, “he has been able to see the future of sport long before others even began to consider the possibilities. Dr. Edwards is a true visionary.”